Archaeological Excavation, Leintwardine Herefordshire

The excavation was undertaken on the site of a new building on the western flank of the Roman road (the modern A4113 High Street) connecting the fortified vicus (civilian settlement) at Leintwardine (Bravonium) with the Roman town of Wroxeter (Viroconium).

In Brief

Services: Archaeological Evaluation; Archaeological Excavation

Location: HerefordshireKey Points

- Archaeological Evaluation revealed a series of cut features close to the line of the road, representing two phases of Romano-British activity separated by a period of abandonment

- Subsequent Archaeological Mitigation phase

- Confirmation of the presence in this part of Leintwardine of at least three phases of Romano-British activity

- Urns uncovered, one of which contained parts of the skull, spine, pelvis, legs and feet of a 25-40-year-old of indeterminate sex

- Exceptionally well-preserved fragments of Roman pottery were revealed

Summary

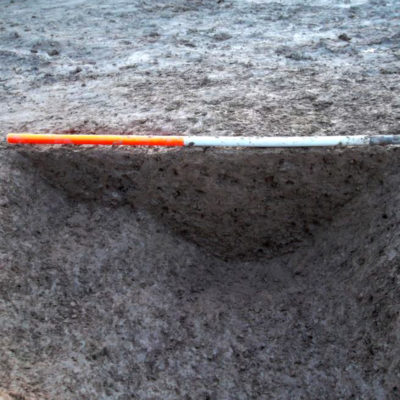

Archaeological field evaluation of the site revealed a series of cut features close to the line of the road, representing two phases of Romano-British activity separated by a period of abandonment. Fine dark grey ware pottery found in the base of a linear feature dated to the 1st -2nd -century AD whilst a single fragmentary vessel also recovered exhibited evidence of heat exposure and was interpreted as the remains of a cremation vessel.

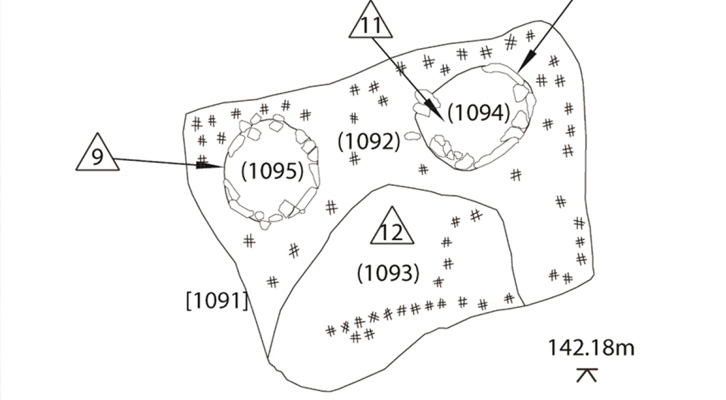

The excavation phase confirmed the presence of at least three phases of Roman activity in the later 1st –mid-2nd century AD. Three cremation burials found at the far south end of the site strongly suggested the area was part of a larger roadside cemetery adjacent to the present High Street on the line of the important north-south Roman road forming part of Watling Street West between Caerleon and Chester).

Ditches parallel to High Street and running west-east appeared to separate the cremation area from what seemed to be agricultural activities in the northern part of the site, containing several substantial ditches running roughly north-south along the roadside and a number of pits. Evidence of crop-processing, woodland disturbance and landscape change was found, with a diversity of charcoal remains recovered from both pits and ditches, many of which were also found to contain exceptionally well-preserved fragments of Roman pottery.

A cremation pit contained the lower parts of two urns, whilst a pit about 1m to the north had a single intact urn. All three are thought to have been manufactured locally in the 1st -or early 2nd -century.

One of the urns contained parts of the skull, spine, pelvis, legs and feet of a 25-40-year-old of indeterminate sex. The relatively small quantity of bone is consistent with a ‘token’ burial typical of the Late Iron Age/Roman period. A lack of tooth roots and very small hand and foot bones may reflect the manner in which the bone was collected for burial.

Radiocarbon dates obtained from the bone placed the burial at the very end of the Iron Age or in the early Roman period while the pottery was consistent with a 1st -or early 2nd -century date.

The complete rim and neck fragment of a glass unguent bottle in blue/green glass was also recovered and, whilst a secure date could not be proposed, it would appear to be of the 1st -2nd century; the inclusion of unburnt unguent bottles in funeral rites was not uncommon at this time.

The site was abandoned at some point in the mid-2nd century and substantial quantities of pottery dumped in the ditches. The date of this abandonment roughly coincided with that of the auxiliary fort at Buckton and the fortification of the town.

Results

Cremated remains provided an opportunity to examine burial practices in a rural area, away from the southeast of England, during the Late Iron Age to Romano-British transitional period when cremation burial became more frequent, possibly associated with Roman influence, although native traditions may also have continued in some regions.

Most of the deposits at Leintwardine contained small quantities of bone which was generally too fragmented to identify as definitely human. Two cremation urns containing no identifiable human bone may have been associated with ‘cenotaphs’ or ‘memorials’, although it is possible that one may have been a grave offering meant to accompany the other rather than containing a burial in its own right.

Another urn contained relatively large pieces of bone, with little evidence of fragmentation, and parts of the skull, spine, pelvis, legs and feet could be identified as belonging to an unsexed adult aged 25-40 years at the time of death.

The predominantly buff/white colour of the bone shows it was burnt at a high temperature with enough oxygen available for long enough to ensure oxidation, suggesting the community had access to adequate supplies of suitable fuel, probably oak, and the skills and knowledge required to construct and tend a pyre effectively.

The most significant aspect of these results is that they may demonstrate the adoption of Roman customs by the local population in a comparatively remote location. A transition towards cremation burial occurred in the southeast of England during the Late Iron Age, from the mid-1st century BC, which may have been associated with Roman influence.

The burials at Leintwardine may thus either indicate rapid and early adoption of a new burial rite in a rural area or represent the continuation of existing native burial practices